Graves, Cannons, and Fog: Reflections on the 2023 Bioarchaeological Field School of the University of New Brunswick, Canada

When I set out to Canada last summer to participate in a bioarchaeological excavation led by Dr. Amy Scott from the University of New Brunswick, I was prepared to learn about groundbreaking archaeological methods and innovative, ethical approaches. I was, however, not prepared to be greeted by a woman carrying a chicken and the sound of cannons.

This was the moment that I realized that the bioarchaeological field school was not just going to be interesting in itself but that the setting of the excavation at the Fortress of Louisbourg was a rather unique one.

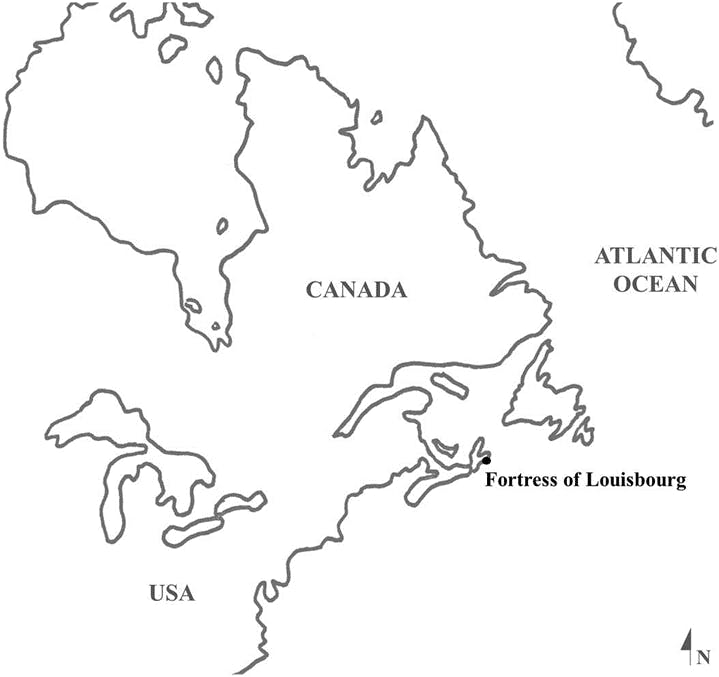

Louisbourg is an eighteenth-century French fortress located on the east coast of Canada. The site, as it can be visited by tourists today, does not only make the general history of an eighteenth-century fortress available to the public; it also incorporates many other stories – some hidden, some visible. The site’s uniqueness lies in its many layers of history and in the many ways this history is told.

Map indicating the Fortress of Louisbourg. (Scott et al. 2019, 92)

The Fortress of Louisbourg was only occupied for about 40 years, between 1713 and 1758. It provides a remarkable window into the time when Louisbourg was a bustling international harbor and a hotspot for the codfish trade.

Besides its history as a center for international trade, the fortress also tells the story of British and French struggles for predominance in the area. Louisbourg itself was taken twice by the British during its short time of occupancy.

After it was abandoned in 1758, the fortress fell into disrepair and the first extensive archaeological excavation of the site was only initiated in the 1960’s. At this time, it was decided that parts of the fortress would be reconstructed as it would have looked during its height in 1744.

High unemployment numbers among former coal miners in the area led to the idea to employ these miners for the reconstruction work, as well as for further excavations, with the aim to make the fortress into a historical site for tourists (Johnston 1999).

Today, the Fortress of Louisbourg is the biggest tourist attraction in the area.

During the summer months, when the number of visitors increases, full-time reenactors inhabit the fortress. The reenactors guide and interact with visitors while showing them how daily life in the 1740’s might have looked: they keep animals, bake bread, and tend to other housework. The lives of the soldiers once stationed at the fortress are also depicted: the reenactments even include the daily firing of muskets and cannons.

The fortress has become not only an eighteenth-century historical preserve, but a site that also teaches visitors about archaeological work and reconstruction practices in the 1960’s.

The Fortress of Louisbourg has emerged as a heritage site that connects multiple histories and identities.

While working on the site, I had the chance to engage with people who all had vastly different personal connections with Louisbourg. Some happily remembered being at the fortress in the 60’s because they or somebody they knew worked on the reconstruction, while other visitors associated anything but good memories with that period.

The area where the fortress now stands had been home to a number of farmsteads built in the centuries after its abandonment by the French. In the 1960’s, these families were driven out and had to move away while their homes were demolished to make room for the revived fortress. From other encounters during my time at the site, I learned about family histories, reaching back to the French occupation of Louisbourg in the eighteenth century. Others simply told the story of how working in the fortress as an interpreter, as the reenactors are referred to on the site, has become a fixture in their summers.

The reconstructed area of the Fortress of Louisbourg. (Photos taken by the author)

Even visitors without any obvious prior connections to the fortress often find one soon. Artifacts and archival materials highlight the great global trade networks of the eighteenth century, giving almost every tourist something to relate to.

I, too, had my own sudden and personal moment of connection to Louisbourg. A few days after my arrival, I was confronted with a Westerwälder earthenware sherd lurking in a corner of the pottery collection. While the small grey-blue sherd was unspectacular to my colleagues, it reminded me of home and – as cliché as it sounds – of Sauerkraut. I grew up on the outskirts of the Westerwald, and this type of pottery is still used in my family’s home for making Sauerkraut over the winter.

Rhenish stoneware from Louisbourg. (Prieto-Martínez 2023)

Example of my family’s Westerwälder stoneware. (Photo kindly provided by the author’s parents)

Sauerkraut I certainly did not eat in Nova Scotia, where I was hosted in the kindest way by my Canadian colleagues. Instead, they introduced me to their local cuisine, including delicacies such as poutine, crab, and Caesars (a clamato-based cocktail).

Yet, the story of my encounter with the Westerwälder earthenware sherd highlights something else that makes Louisbourg so special as the setting of an archaeological excavation.

In so many ways, the fortress is about the life stories of all the different people who have been connected to it in different ways throughout its history.

The author’s first Poutine. (Photo taken by the author)

A crab meal at the Crab Festival in Louisbourg. (Photo taken by the author)

One part of the research that helps us understand the lived experiences at Louisbourg, is the bioarcheological field school run by the University of New Brunswick. The field school focuses on what is, from the perspective of the landscape, the most visually stunning area of the fortress. However, this area is also the most endangered part.

Louisbourg lies on a small peninsula that narrows towards the tip. In recent years, the tip of the peninsula has been increasingly threatened by coastal erosion. The impact of Hurricane Fiona in 2022 is still clearly visible. This particular piece of land was also used as a burial ground of the fortress. The rapid erosion of the coastline makes the excavation and preservation of the individuals buried there both urgent and unavoidable. In 2016, a collaborative project was established between Parks Canada and the University of New Brunswick to save as much of the peninsula’s remaining burials as possible.

What sounds like, and what for some short weeks in the summer also is, an incredibly beautiful scrap of land reaching out into the North Atlantic, is, in reality, a rather rough terrain for most of the year.

“Foggy!” was probably my most repeated response to the question of how it was during my weeks at the fortress.

The thick fog would erase the world around the excavation … (Photo taken by the author)

Though we always had rain gear lying close to the trench, some days, we did not even have time to reach for it before we were soaked through. The incredibly thick fog and suddenly appearing thunderstorms that pushed us to pack up in seconds were stark reminders of the harshness and the struggle that nature brings to this excavation – and would have brought to the lives of the inhabitants of the fortress in the eighteenth-century as well as the miners working there in the 1960s.

… Just to be suddenly driven away by sunshine a couple of hours later. (Photo taken by the author)

The archaeologists are constantly working against time and nature when they each year try to rescue the most endangered burials without destabilizing the coastline even further.

Working with human remains, however, raises many ethical questions.

While it is obvious that these burials have to be excavated, with reburial in a safer location being the ultimate aim, different belief systems collide at this eighteenth-century site. The excavation is run in close cooperation with local communities and Parks Canada, who are responsible for the national site, as well as with other stakeholders. Parks Canada employees answering questions from tourists are as much a fixture on site as are visits by members of the local Mi’kmaq communities, who also conduct a cleansing ceremony of the site and its archaeologists each year.

The coastline at Louisbourg was severely impacted by Hurricane Fiona in 2022. (Photo taken by the author)

Treating human remains with respect is demanded of every archaeologist working on the dig, as well as from every visiting tourist.

The excavations on the tip of the peninsula are located just a short stroll from the reconstructed fortress, and while visitors are more than welcome to come by, have a look, and ask questions, there is a strict ‘no photo’ policy on site. It is also expected that members of the excavation team understand that recovering these burials is a sensitive matter about which some may disagree, depending on their own beliefs and connection to the site. Such concerns, especially if they are voiced by people visiting the site, are taken seriously, and quite often, open and interesting conversations emerge between team members and visitors.

Taking different experiences, beliefs, and understandings of the site and its history into account can also have practical results for the excavation. For example, burials that seem to have a connection to indigenous communities simply stay in situ, as this is what the local Mi’kmaq community has wished for them.

While students in the field school learn practical archaeological skills, they learn just as much about the various ethical issues that can arise when working with human remains.

Each one of us was also confronted with our own thoughts while excavating. Thinking about, studying, and working within the field of bioarchaeology might be one thing; excavating the actual grave of a human being is quite another. It can be a very challenging experience. Working so closely with the remains of the people who inhabited the fortress in the eighteenth century, suddenly made these historical lives real and tangible. Having worked in the field of archaeology before, it was an experience I was prepared for, and yet one that was in many ways surprising.

While recovering and reburying the individuals is the first priority, the scientific research carried out by the team is also very present at the site. The uncovered individuals are subject to bioarchaeological studies, which have the potential to greatly expand our understanding of what life would have been like at the fortress.

The bones often reveal different aspects of history than do written sources, and it is a thoughtful combination of source materials that makes the storytelling at Louisbourg so enriching. In Louisbourg, interdisciplinarity is highly encouraged, and it is not uncommon to see local historians excavating or archaeologists asking for historical sources from the archive.

Bioarchaeology adds its own layer to the interpretation of the fortress.

With all the new scientific developments in the field, such as isotope studies and genetics research, bioarchaeology enriches our understanding of health, stress factors, and the impact of labor on the body throughout history. Besides this, it also adds to the general understanding of the demography of a place like Louisbourg.

But it would not be Louisbourg if this innovative scientific research did not circle back into the multiple stories of the fortress. Many archaeological and bioarchaeological finds are used to improve the presentation of the site – today, all reconstructed objects in the fortress are based on archaeological finds! The findings are also used to improve the life stories told by the reenactors, which have been diversified in recent years.

For me, participating in the excavation was not just a great opportunity to learn more about the approach to burial archaeology developed by Dr. Amy Scott and her team. It also provided a rare chance to see how historical sources and archaeology can build on each other and how they are tightly woven together in an actual interdisciplinary approach.

My time at Louisbourg taught me a lot about archaeological methods but also about the ethical discourses connected to them. It taught me a lot about historical archaeology, but also about how academic research can be transferred to a wider public.