Documents, their Absence and Power: An Immersive Experience at the National Archives in London

Little did I know, when I set out on my journey from the Cologne-Bonn Airport to London on the morning of April 4th, 2023, that I was about to face a form of discrimination that many researchers before me have encountered.

Everyone else had already boarded the plane, but I was stuck in the airport awaiting verification of my visa’s authenticity by customs officials in London. It took approximately 40 minutes, during which time I had to sit and wait with my ‘strong’ Turkish passport. To make matters worse, I already had a valid visa in hand.

Waiting to Set Out on my Journey at the Cologne-Bonn Airport

Thankfully, though I had to step onto the plane amid ongoing uncertainty, my visa was confirmed before I landed at London Heathrow.

But that’s not the end of the story. Upon arrival, I was taken to a room where I underwent an extensive interrogation regarding my accommodations and itinerary before finally being granted permission to pass through customs.

Since my arrival coincided with the Easter season, I had limited time available before the archives were scheduled to close for public holidays. As is often the case on archival trips, there was no time to dwell on what had transpired. I refused to yield to the pressure and abandon my goals. Instead, I persevered and continued to make progress.

A Façade of the National Archives of the United Kingdom (Photo by Author)

Finally, I made it to my destination. The first two days were dedicated to deciphering the system in place, acquainting myself with the available resources, connecting with helpful individuals, obtaining a reader’s card, and exploring the research halls.

Before long, however, I encountered yet another unsettling obstacle.

Thankfully, this one was a bit more typical for archival researchers. My doctoral research project examines the enslavement experiences of children and the intricate network of slave dealing that was prevalent during the latter half of the nineteenth century. While considering these broader historical trends, my work is also grounded in a particular place. Specifically, I aim to shed new light on the complex dynamics involved in Children's experiences in Istanbul during the period of the Ottoman Empire. Despite the gusto with which I set to my task, I was dismayed to confront the reality that the Foreign Office records about the Nineteenth Century Ottoman Empire had yet to be digitized.

Once again, there was no time to pause and lament; I had to dive into the task at hand.

I already had a rough idea of what I was looking for in the archive. However, when it came to the correspondence of consuls and Foreign Office officials in the Ottoman Empire, two separate indices were available. The first index was a set of images wrapped around microfilm.

There were dozens of microfilm spools to sift through and so little time to do it!

Realizing how long it would take to complete this task, I 'turned on the (professional) charm' and set out in search of assistance. Again, however, my efforts were in vain. I have not received any training on how to operate a microfilm machine, and no one was available to teach me. So, it was time to get my hands dusty and figure out how to work with the materials myself.

As I began manipulating the microfilm cartredges, that feeling of deep embarrassment, which often accompanies noisy projects in quiet libraries, fell over me. As plastic clashed against plastic and spools of recording tape shook like an angry rattlesnake’s tail, I thumbed through the cartridges.

I conducted rough searches for keywords like “child,” “Arab,” “Circassian,” “kidnapping,” and “slavery.” Then, I turned to the other indices that provided dispatch numbers, which were crucial for locating the actual documents. This process was time-consuming, and the available magnifiers were relics of a bygone era, requiring manual adjustments for both focus and zoom. Thankfully, the documents for which I was searching were in English; otherwise, deciphering their meaning might have been even harder.

A Microfilm Machine at the UK National Archives (Photo by Author)

After reading through various observations on domestic slavery and the slave trade, I noticed a recurring focus on a particular topic: child abduction. It seemed that children were being kidnapped for various motivations and from numerous places.

One entry, in particular, caught my attention. It read, "Armenian children kidnapped by Jewish merchants." Unfortunately, this entry only had a summary in the index. After ordering the relevant catalog page using the appropriate dispatch number, I found myself stumped once again: I discovered that the page containing the summary had been torn away! Who would have done that? Was it just an accident, or was it on purpose? Who might have wanted to prevent officials, researchers, or the general public from accessing this material? I was stumped and a bit annoyed.

I had finally caught a break, and then… Now what was I supposed to do?

I found an expert Foreign Office archivist and asked for additional information. I was in a race against time. I had only two days left, and I was determined to find this crucial material at virtually any cost.

A Snapshot of a Partial Citation in the Archives (Photo by Author)

When the archivist quipped, “You are aware that you’re looking into Foreign Office records, aren’t you?” I couldn’t fully grasp what she was implying. However, she added something afterward: “We don’t have the original copies of all the Foreign Office records here. Some dispatches tend to be torn or disappear anyways... The file you are looking at is just a copy; the original is located at the Foreign Office building itself. If you’d like, we can place an order for it.” Delighted, I said, “Yes, let’s order it immediately.” Miraculously, the order was fulfilled promptly.

In yet another frustration of fortune, however, I soon discovered that the relevant page was also torn away in the actual document. My hopes of finding the sources I needed were dashed once again.

The question re-emerged: Who could have wanted to prevent access to this document, and why?

As any seasoned scholar can attest, the pursuit of knowledge knows no bounds, and the journey is perpetual. With my research trip drawing to a close, I savored the remaining moments of my time in the United Kingdom, embracing the opportunity to delve a bit deeper into its cultural tapestry.

While enjoying a delightful pub outing in Edinburgh with a former BCDSS fellow, I shared my experience in London. She suggested, “In the UK, there is a Freedom of Information Office, and you could explain the situation to them and request the document. Perhaps they can assist you.”

A Photo from the Micro-Film Index

Of course, I took her advice and submitted a form that explained my situation. The request appeared to be processed quickly, but I am still waiting to hear back: It’s been around seven weeks now.

In the end, however, the fact that I don’t yet have ready access to the proper documents does not mean I will stop telling the stories of kidnapped children.

Why am I sharing these reflections with you? By writting about my most recent archival experience, I hope to ignite a flame of resilience within each of you, urging you to persevere in your own quests for knowledge. Let not the tumultuous winds of external political circumstances, whether past or present, dampen your spirits.

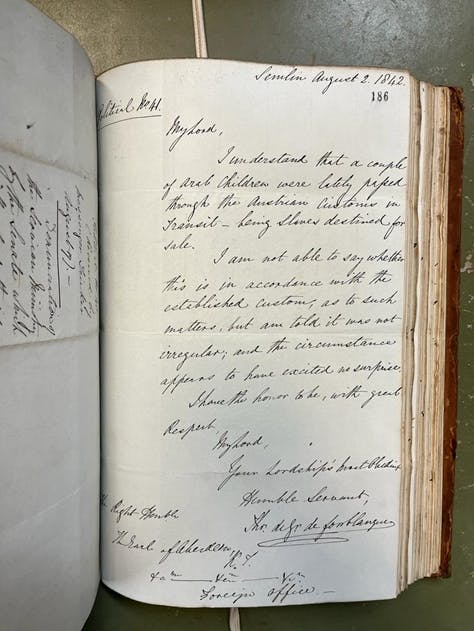

A Letter from August 2nd, 1842 about 'Arab Children' and 'Established Customs' preserved in a large folio (Photo by the Author).

The more I share my experiences on this most recent archival trip with my fellow researchers, the more ideas I receive about how to chase down this missing document. Just recently, a cluster professor suggested that I explore archival records to find information about researchers' previous inquiries. Hopefully, I can then compile a comprehensive list of potential researchers with whom to correspond.

One thing I've learned from this process is that, especially as a junior researcher, it is crucial to share your experiences extensively with peers, colleagues, and mentors to reap the benefits of their collective experience.

Fortunately, the fragmentary nature of the documents I discovered did not comprise the over-arching mission behind my archival investigation. I diligently collected a diverse array of fascinating materials that contained insights into the intricate relational dynamics at play in nineteenth-century Ottoman domestic slavery. I also learned a lot about the trafficking of enslaved children and the global interconnections that were documented by British consular authorities of the nineteenth century.

My discoveries included captivating instances that warrant further exploration: For example, I learned about the experiences of İbrahim, an enslaved black youth, and Cemal, a young Circassian slave. To my knowledge, the lives of these youth have yet to be engaged in detail by historians. I eagerly anticipate delving deeper into their context and learning of their stories.

I wish to express my profound appreciation to the BCDSS for providing me with the opportunity to visit the National Archives. As previously expressed, I am also profoundly grateful for the collegiality and willingness to share that has been expressed by my BCDSS colleagues, both among my peers and by more senior researchers.

All that said, my primary intention in sharing my most recent archival endeavors with the readers of the BCDSS Blog is driven by the desire to highlight a pertinent issue: Namely, the limited mobility experienced by many individuals in their pursuit of knowledge.

Unfortunately, transnational political circumstances continue to impose significant obstacles upon researchers and their scholarly pursuits, even when they possess all the requisite correspondences, invitations, and permissions. As this account attests, I, too, have been affected by these realities, both by historical political circumstances dating back around 150 years and the transnational complexities of our own age.

Documents, especially of the 'official' or governmental variety, have power.

They had power during the period of the Ottoman empire: They could preserve, highlight or erase people's stories. They have power today: They can impact not only the ability of researchers to access the materials they need to listen for silenced voices in historical narratives, but the lives of millions of people around the globe. Their presence, like their absence and the processes in place to mediate access to them, can be felt and that should matter to us.